© Jim Low 2018

In his 1946 poetry collection entitled The Dosser in Springtime, Douglas Stewart includes the poem Rock Carving. This poem, unfairly treated in my opinion by Peter Read in his book Belonging, published in 2000, has as its stimuli the rock engravings of a fish and a kangaroo.

While night fishing in waters north of Sydney, Stewart reflects upon creativity, its longevity and questions whether artistic accomplishment requires an audience.

‘How we cut our thought into stone as best we can

Laugh at pain, and leave it to take its chance.

Maybe it’s all for nothing, for the sky to look at,

Or maybe for us the distant candles dance.’

He sees the rock engravings as ‘living a hard strange life of their own’ once they are completed and their creator has gone. His use of the plural ‘we’ shows he too shares these artistic predicaments. In his poem Stewart says that he would have liked to talk to the rock carver, believing that their fishing and art would have comfortably provided them with conversation starters.

The possibility of ‘the distant candles’ continuing to dance for the rock carvings, thereby guaranteeing their survival, seems assured in Stewart’s poem. He has seen them and his poem is evidence of their existence.

The delicate image of ‘the distant candles’ as they keep glowing, despite the winds of time, effectively highlights the fragile nature of any art form.

Once completed, the creative work is faced with the quest for survival. How many indigenous rock carvings, like the fish and kangaroo, survived generations only to be destroyed with the intrusion of settlement?

As Stewart confidently states in his poem:

‘They glow with immortal being, as though the stone fish

May flap and slither to the tide, as though the great ‘roo

May bound from the rock and crash away through the bush.’

I can only hope that the same is true for Stewarts’ poetry, their ‘distant candles’ continuing to dance through the years.

And while on the subject of bounding kangaroos, many years ago I read about a rock carving of a kangaroo in my local area. Located early last century on the Blue Mountains escarpment in the Hawkesbury Heights region, I recently came across a rough map showing its approximate position in the escarpment bushland. I even had a line drawing of it, courtesy of Eugene Stockton’s valuable book Blue Mountain Dreaming. I have ventured into the bush many times before, looking for things, while armed with more precise information than this. And I still have returned disappointed. So, when I started my search in bushland above Shaw’s Creek last week, I was not too confident of an outcome.

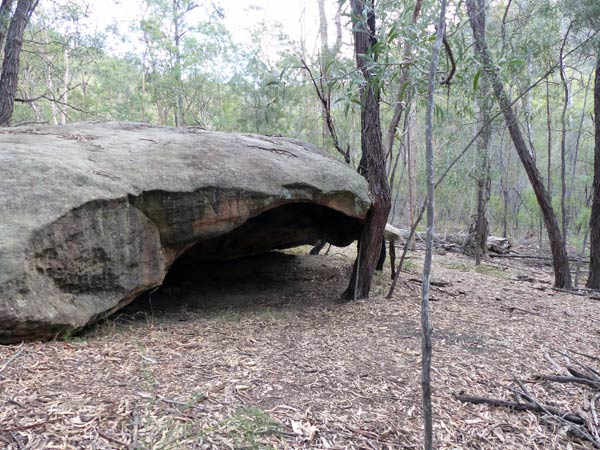

A pleasant Autumn day, the recurring cloud cover helped to soften the afternoon glare and erase those distracting shadows. Eventually sighting a rather large rock surface, I headed towards it, feeling confident that this was definitely an appropriate, natural canvas to accommodate a kangaroo carving.

The search now began, but the more I looked the more my ‘great ‘roo’ seemed to elude me. Had it literally. on my approach, bounded from the rock and crashed through the bush, just like Stewart imagined the powers of the one he saw back in the 1940s? I circled the whole rock, discovering a space under the rock where Aboriginal people could have comfortably found shelter. This natural feature made me even more certain that I was at the right location. I returned above to the large rock ledge and, this time, got down on my hands and knees and began to feel its surface. Still no success. I stood up and, after taking some photographs of the rock and its bush setting, reluctantly decided it was time to leave.

I returned once more to the ledge and got down again on all fours for one more attempt to discover this elusive, ‘great ‘roo’. From this humble, prayer-like position I remember looking up to the sky and silently expressing my desire to see the carving. I stood up and took in the beautiful location. One more look down on the rock where I stood and… My eyes behaved like a camera, suddenly coming into focus. There it was! I couldn’t believe it. I was looking down on the engraving of a bounding kangaroo, roughly a metre in front of me. I quickly took some photographs, genuinely worried that this creature would bound from the rook and disappear into the surrounding bush. However, to borrow Stewart’s beautifully perceptive words, it continued to ‘glow with immortal being’.

Stewart’s ‘distant candle’ image reminded me that six days prior to my seeing the carving, I had celebrated a birthday. The sighting of the rock carving was for me a very special gift.

I plan to return to this place very soon. It is not that far from where I live. I shall look closely for accompanying rock markings noted in the Stockton drawing to which I previously referred. I also would like to measure the carving.

I shall conclude with a few thoughts and questions that came to mind after seeing the rock carving. What is the age of the carving? Could more than one artist have been responsible for its creation? The kangaroo’s life-like size and realistic proportions could suggest the possibility of a corpse being used as a template to trace the shape more accurately. How appropriate is the carving’s positioning and location? Even though I had some difficulty finding it, its exposed position suggests that it is meant to be seen, there is an intended audience for it, not just the sky.

Just like the fish and kangaroo in Stewart’s poem remind me of the self sufficient lifestyle of the Aboriginal people before 1788, the same is true of this large kangaroo at Shaw’s Creek.

Is it a visual indication that kangaroos are plentiful there? Is it more general, perhaps suggesting that this is an area of plenty – fertile, healthy country? The proximity to Shaw’s Creek could also suggest this. In marking the rock, does this indicate a sense of belonging, by the carver, to this place? Has the engraving religious or cultural significance to this area and its people, or is it purely a piece of art for no other reason than to appreciate and enjoy?

None of the above thoughts or questions in anyway seek to devalue the importance of this special cultural site. To borrow and hopefully not abuse the words of Douglas Stewart , I’ll close with the following:

‘For here is … a ‘roo that leaps

Nowhere for ever, and … can be touched with the hand.’

The artist behind the rock carving has left his ‘mark on stone like a mark on time’.

I greatly value the opportunity I was given to see this rock carving in its bush setting.

© Jim Low 2018