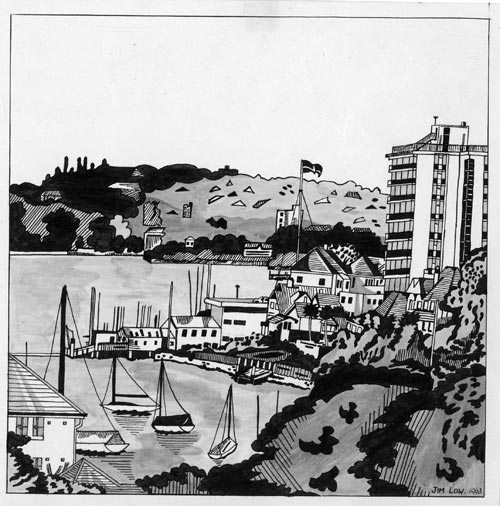

In 1963 I drew a picture, using black ink and water, of the view from the back window of my High Street home in North Sydney. My drawing featured a partial view of Careening Cove as it joins Sydney Harbour. Private yachts are scattered around Careening Cove at safe moorings. The harbour water view extends across to Rose Bay. It was from there that we often saw tiny flying boats make their tenuous run before finally rising into the distant sky. The flag of the Royal Australian Yacht Squadron can be seen flying above Kirribilli.

This suburb, at the time of my drawing, was uncomfortably accommodating change. New, high-rise, water-front apartments loomed over older style, single residences, all jostling for position in this crowded landscape. Ruth Park believed that ‘Kirribilli was probably Sydney’s earliest victim of haphazard, greedy development’, comparing ‘its ruined profile’ to ‘a broken comb.’ (Park, p 218)

When walking around North Sydney today, it is hard to imagine the area as it was when Europeans first arrived. Covered by thick, native bushland or ‘forest’ to the water’s edge, with few discernible or reliable tracks to follow confidently, initial travel was by water.

Travel over vast, unforgiving oceans had brought The First Fleet safely to this country and remained the sole way back to England. The repair and maintenance of vessels was therefore crucial for the colony’s survival and progress in this unfamiliar landscape.

A convenient place to carry out such repairs was soon found on the northern side of the harbour. This narrow inlet quickly became known to the new intruders as Careening Cove. No one imagined that it already had a name. The Cammeraygal, the Aboriginal people on whose country this cove was situated, had named it Wia Wia.

Although Careening Cove was convenient to Sydney Cove, it was considered far enough away to discourage the sailors’ temptations for women and drink and allow them to get on with their work. The word careen comes from the Latin word meaning keel. When careening a ship, it has to be carefully manoeuvred onto its side, thereby allowing sailors to clean the hull and carry out necessary repairs. At the head of Careening Cove were tidal flats, allowing ships to be careened with relative ease. There was also a fresh supply of water from a creek that ran to the cove.

In June 1789 The First Fleet’s flag ship Sirius was ‘taken to a cove on the north side of the harbour, much more convenient for giving her those repairs for which she now stood so much in need’. (Hunter, p109)

These are the words of John Hunter, the captain of the Sirius. While returning from the Cape of Good Hope with supplies for the colony, the Sirius experienced a very severe storm near Tasmania. The resulting damage was the reason for Hunter’s decision to have significant repairs carried out on the ship’s weakened hull, on returning to Sydney. This was to be carried out at Careening Cove.

A ‘careening cove’ named on an early map was located where Mosman Bay now is. So there is some confusion as to where the initial, urgent repairs to the Sirius were actually done.

The following information, from the accounts of Newton Fowell and Hunter, establishes Careening Cove’s close proximity to Sydney Cove as a deciding factor. Their accounts convince me that the repairs to the Sirius were carried out in the cove next to Neutral Bay and still named Careening Cove today.

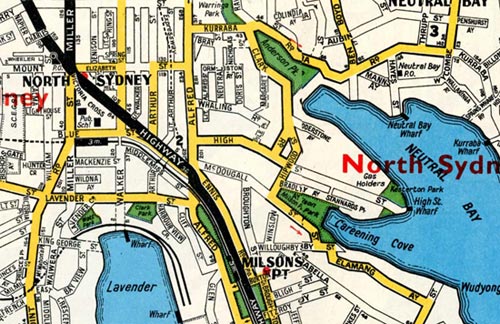

Newton Fowell was a midshipman on the Sirius. In letters he wrote to his father, he tells how ‘A Convenient Place on the North Side of the Harbour Was fixed on’ to repair the Sirius. (Fowell, p114) He explains how, if someone wanted to go to Sydney from there, they could rely on getting a boat once every three or four days. If this was not convenient a person could walk to where they were ‘abreast’ of Sydney Cove and wait for the first boat sighted to take them across the harbour. (Fowell, p115)

Hunter tells of Francis Hill, one of the master’s mates, who was given permission to go to Sydney Cove on the night before the Sirius was taken back there to have the above deck repairs completed.

‘(Hill) went over, and was the next morning early put across to the nearest part of the north shore, intending to walk round to the ship, a route which had been often taken by many of our gentlemen, and was not more than an hour and a half’s walk.’(Hunter, p113)

This only makes sense if you walked around what is now the Kirribilli shoreline to the cove. Both these accounts rule out the feasibility of Mosman Bay being the location for the Sirius repairs.

The close proximity to Sydney Cove was an important reason for choosing where the Sirius was repaired. The choice of Careening Cove allowed Hunter to keep abreast of the progress of the repairs while continuing his other official duties.

The fear of the local Aboriginal population probably played a part in the decision as well. At Careening Cove the sailors were not very far from help if it was required. Newton Fowell notes that, ‘The natives were very numerous at the Time at all parts of the Harbour’. (Fowell, p115) Hunter was aware of the possible danger in which this placed his crew, especially when they moved about the bush unarmed. ‘We have much reason to believe,’ he wrote, ‘that they are disposed to take the advantage of those they meet without fire-arms.’(Hunter, p113) Some of these fears were not unfounded. The previously mentioned crew member, Francis Hill, never made it back to the Sirius after his visit to Sydney Cove. It was strongly believed that he fell foul of the local Aboriginals.

Prior to the arrival of The First Fleet of convicts in 1788, harbour inlets like Careening Cove provided the indigenous people with a consistent supply of fresh food. The word Kirribilli is believed to be a corruption of an indigenous description for ‘a good place to fish’. Intrusion into these places by the new arrivals quickly threatened the indigenous people’s access to the fish, plants and the animals found there. Traditional places of cultural and religious significance were damaged or destroyed. Diseases silently spread with devastating consequences for the indigenous population.

Around Careening Cove the new intruders began to change the landscape. Ground was levelled to provide an area to store supplies from the Sirius. Trees were cut down to build a wharf and supply the necessary timber to repair the Sirius and other vessels. These changes that came with the initial careening of ships were not going to stop. The water quality in the cove and the fresh water creek began to decline. The pristine days were under threat.

By the late 1800s the tidal flats in Careening Cove were polluted with so much nasty smelling rubbish that reclamation of the flats could no longer be deferred. Local residents found it unpleasant to live there.

When I played in this area in the 1950s, the tidal flats were gone and so was the creek. A stone, seawall stretched across the cove and the land behind had been filled in to make Milson Park.

The fresh water creek that flowed into Careening Cove was called Rainbow Creek. This colourful name apparently came from the HMS Rainbow which was careened at the cove in the 1820s.

Writing in the early 1930s, Livingstone Mann remembered drinking from the creek around 1870.

‘Many a time on a hot day have I quenched my thirst from the clear stream called Rainbow Creek that ran through St Leonards (where McIntyre’s Pictures now stand) onward to Careening Cove.’ (Mann, pp191-192)

Mann was the grand-son of Sir Thomas Mitchell and son of explorer and surveyor John Frederick Mann who accompanied Leichhardt on his second expedition. The early tent picture theatre which Mann referred to was built in 1912 and was situated on the corner of Mount and Arthur Streets. This is not far below Rainbow Creek’s source, believed to be near the present day site of the MLC Building on the corner of Mount and Miller Streets.

The English writer Roger Deakin once described the source of a river as ‘the tear duct of the earth’. This seems sadly appropriate when remembering Rainbow Creek, this once delightful and valued little life source that babbled and bubbled its way down to Careening Cove. And, of course, it had done so for many years prior to the arrival of The First Fleet.

When I was a child in the 1950s, the only possible evidence that a creek ran this way was the concrete, stormwater drainage canal that separated Milson Park from Bradly Avenue and emptied into Careening Cove.

There was a wild space that ran behind the houses in McDougal and High Streets, going as far as the back of the Continental Hotel in Alfred Street. We accessed this unofficial play area from friends’ backyards or two dirt tracks that ran off Hipwood Street. From memory, these tracks provided access to the backyards of the houses in High and Hipwood Streets. The track that went behind the buildings fronting High Street ascended one ridge of the gully along which the creek would have flowed. I remember that this wild space, where we played, was also being used by the local council to dump waste fill.

There was another open space behind the Orpheum Theatre and other neighbouring businesses along the Pacific Highway. This area extended up to where Little Arthur Street cut across the rising landscape on its way to where the North Sydney central business district is located today. The creek would have once run through part of this area. This was also where an old Morton Bay Fig tree stood.

Unfortunately, I have no memory of Rainbow Creek. It had already been buried in stormwater piping, under roads and buildings. And the Warringah Expressway sealed its location for ever.

After repairs to the hull of the Sirius were completed, the ship was towed from Careening Cove to Sydney Cove on 7 November, 1789. There the final, above-deck repairs were to be completed. A few days prior to this, John Mara, a crew member, was sent to fill some containers from ‘a run of water near the ship’.(Hunter, p112) If the Sirius was repaired in Careening Cove adjacent to Neutral Bay, as I believe, then this could perhaps be the first recorded mention of the fresh water stream that would later be called Rainbow Creek.

It was getting dark when Mara entered the bushland, presumably to retrieve water well away from any salt contamination from the sea water in the cove. Before reaching the stream and having imbibed before he left the ship, he lay down and went to sleep. Disorientated when he awoke, he became lost in the bush and was not found for three days. A boat, which happened to include Hunter in its crew, found him after hearing his cries from the north side of the harbour. This incident also highlights how easy it was to become lost in bushland relatively close to the main settlement.

The margin of Careening Cove today is packed with residences of varying sizes and population densities, all eager to capture any sighting of the harbour. There are still businesses on the shoreline maintaining some maritime connection.

Trying to imagine the area as it was when Europeans first arrived becomes more difficult each time I visit the place that has so many childhood memories tucked around it. And as for Rainbow Creek, well it was not even a memory when I ranged over this childhood landscape in the 1950s.

© Jim Low

References:

- Fowell, N. : The Sirius Letters, A Daniel O’Keefe Production, 1988

- Hunter, J.: An Historical Journal 1787-1789, Angus and Robertson, 1968

- Mann, L. F.: ‘Early Neutral Bay.’ Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol xvii Pt iv 1932, pp183-208.

- Park, R.: Ruth Park’s Sydney, Duffy and Snellgrove revised 1973 edition, 2000