© Jim Low

Jim Harper was born in Coonabarabran in May, 1878. As a child, he moved to Angledool in northern New South Wales with his parents James and Lillias Harper. This area was first settled by Europeans in the late 1840’s, after Sir Thomas Mitchell’s exploration in 1846. Angledool was originally Angledool Station and later became a private township. The site of the town was about thirty kilometres from the Queensland border and approximately one hundred kilometres north of Walgett.

Most of Harper’s life was lived in the Angledool district. He left school at the age of thirteen and went to work as a station hand on Nullawa Station. Later he was to reflect on this, saying: “I was plucked from the Tree of Knowledge before I was ripe.” (Memories, p 30)

In 1894 during the Shearers’ Strike he was working at Currawillinghi shearing shed and remembered the amount of unrest in the area. In 1915 he married Edith Pratt at the Angledool Post Office, the ceremony being performed by the local post master. They had three daughters and a son. His wife died in 1930 during a typhoid epidemic which spread through the region.

During his life Jim Harper gained a reputation in the district as a poet and writer. His published works include Splashes From The Narran which was set up and sponsored by The Workers Trustees, St Andrew’s Place, Sydney. Although the copy I now have of this publication is undated, the copy in the National Library of Australia is dated 1924. It contains both poetry and short stories. Another of his works is A Hundredth Man And Other Stories, a small collection of short stories printed by the Collarenebri Gazette Print in 1929. Unfortunately a lot of Harper’s poetry was never published.

I first heard some of Jim Harper’s poems in 1972 at North Sydney when a family friend, Thomas McCarthy, recited them to me. In November of the same year I made a recording of the 82 year old Mr McCarthy reciting from memory some of the poems. When asked whether he knew who wrote them he replied, “No, I don’t to be honest.” The poems he recited included The Old Bark Pub, The King, Myall Grove and A Strange Dream. These poems were published in Splashes From The Narran. Mr McCarthy later gave me typewritten copies that he had made of The King and another poem which appears in Splashes From The Narran called The Courtship Of Spooney.

Thomas McCarthy and his twin brother Percival were born in Bairnsdale, Victoria in 1890. They were educated at Barker College in Sydney. Both brothers were medically unfit for service in World War 1. Percival was lame in one foot, the result of a scalding accident as a young child, while Thomas suffered from a heart murmur. After their father’s death in 1924, they went to help manage a family property in the Angledool district. The McCarthy brothers were later to leave the area because of drought and return to Sydney. Neither brother ever married and they were inseparable until Percival’s death in 1969.

In his book Time Means Tucker, ‘Duke’ Tritton makes reference to visiting Angledool during the first decade of the 20th century.

“Like most of the outback towns it was said to be on a river, in this case the Narran. I saw several little depressions in the ground which one of Angledool’s citizens said was the Narran River. In fact, he told me he had seen water in it after heavy rains in Queensland. I agreed that it was a very nice river, and he shouted me a beer.” – Time Means Tucker, H.P.‘Duke’ Tritton, Shakespeare Head Press, Sydney, 1964 p.111

Up until 1996, I had never heard the name Jim Harper and I wavered between the belief that possibly either Tom McCarthy or his brother Percy had written the poems. However, through a brief mention of the books Splashes From The Narran and Memories Of Angledool on the ABC Radio programme Australia All Over that year, I was able to make contact with Mrs Pat Cross of Mehi, Angledool. Over the telephone, I recited sections of The King and The Old Bark Pub which I had heard Mr McCarthy say nearly twenty five years before. What a thrill it was to hear her response: “They’re Jim Harper poems.”

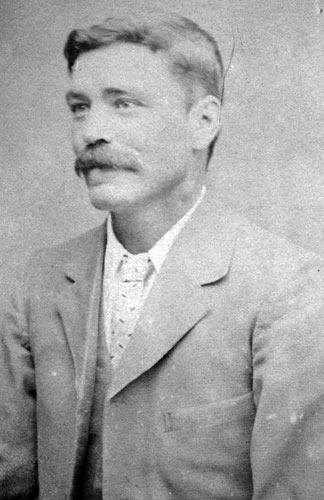

In the 1940’s Jim Harper wrote weekly articles in the Collarenebri Gazette. Mrs Cross has compiled these into the book Memories of Angledool. There is a photograph of Harper sitting with his arms folded and legs apart, wearing a wide brimmed bushman’s hat, three piece suit and tie. The moustached Harper exudes a confident air and appears very approachable.

During the 1970’s and 1980’s I had spent time adapting into song two of the poems which Tom McCarthy had recited to me. The poems were The Old Bark Pub and The King and they each started with a different tune to the one I now sing. In the 1990’s I continued to perform them. After learning of their authorship, I was also motivated to set another five of Harper’s poems to music. As with the first two poems I adapted, for the most part I kept to Mr McCarthy’s versions of Myall Grove and A Strange Dream, despite having now seen the published texts.

Thomas McCarthy died at North Sydney on 15 February 1978. He was a wonderful old man, a true gentleman whom it was my good fortune to have met. I can still picture him as he, with little apparent effort, recollected words heard first by him nearly 50 years before, as a young man, in the drought ravaged north west of New South Wales. I am still of the opinion that he learnt the poems aurally. Although Harper’s poetry was first published around the same time that the McCarthy twins left for the north west, I do not believe that they ever owned or saw a copy of Splashes From The Narran.

Both brothers were very sentimental, keeping many mementos of their past, for example, the hats they wore at Barker College. I believe that Mr McCarthy was more likely to have heard the poems recited by others during his time in the Angledool district and made copies of them so he could learn them himself. I doubt that he ever met Jim Harper. If he had known the author, I feel sure that he would have acknowledged the fact. And his memory was too good to have forgotten. A close study of some of the variations between Harper’s poems and Tom McCarthy’s versions shows only slight variations. I believe that this most likely happened in their oral transmission amongst those who heard the poems and liked them enough to learn them as accurately as possible.

Listen to The King (1907) and read the poem.

When I first listened to Mr McCarthy reciting The King, the image of King Tommy wandering “about the township in a policeman’s cast off shirt” was hard to forget. The description of this Aboriginal elder wearing the discarded clothes of the representative of the laws of another culture made a real impact. Despite the fact that the breastplate signifies the suppression of his authority by another, in Harper’s mind Tommy is proud of “the brass that dangles from a chain about his neck”.

When he made his “first acquaintance with Aboriginals” at Angledool, Harper claimed to “have no hesitation in stating that they out-numbered the white population by a large majority”. [Cross, p.57]

“There was a big camp on the ridge facing the township, and the small white children (of which I was one) were always welcome visitors. Those people young and old, always appeared to take a motherly interest in us, and our own mothers never worried about our safety, so long as they knew we were at the camp.” – Cross, p.57

Harper had been raised having a respect and concern for the Narran Aboriginals. He witnessed the decline in their numbers and the slow destruction of “the old traditions, the pride, the strict moral code, handed down to them by the old warriors”. [Cross, p.63] Harper’s poem provides us with a glimpse of life on the frontier before colonial life brutalized many of the settlers in their attitude and behaviour towards the Aboriginals.

In The King Tommy’s memories return him to “the old wild bush that bred him” where he finds some solace. In another of his Collarenebri Gazette articles, Harper wrote:

“The sight of an Aboriginal man always takes me back to the old days, and I see Tommy, who, in his declining years, was plated King of the Narran Tribe, and his old wife, Maria.” [Cross, p.61]

Harper wrote from his experience of the frontier in Angledool and what he saw happen to the Narran Aboriginals. I have always thought that the first verse of this poem is such a powerful one. It concisely highlights the differences between the two cultures existing on the frontier. European ideas towards the land, characterised by ownership, permanent housing, land clearing and fencing are contrasted with those of the Narran Aboriginals who “roamed the ridges” of this “howling wilderness”. Harper is saying that the lives of these Aboriginals would never be the same again. In the full text of the poem he describes the newcomers as “white invaders” and has Tommy remembering their coming as “that awful first white man scene”.

Listen to The Old Bark Pub (Honest John) and read the poem

The old hotel was built by Henry Hatfield and was run by John Merry. Apparently his daughter was the first white female born in Angledool. When Merry left the old bark pub he only moved a mile or so up the road to New Angledool where he built another hotel. Despite this hotel being soon destroyed by fire, he rebuilt and continued to run a successful business for many years.

Before the first hotel was bought and demolished by the blacksmith, Harper’s family lived in this old building. It stood opposite the Commercial Hotel, which was also built by Hatfield, and was opened around 1880. Harper’s poem would have been based on the memories of older residents who remembered the building when it operated as a hotel. These memories possibly would have included John Merry’s wife to whom Harper said he had spoken. In 1927 Harper became the licensee of the Commercial Hotel and held it for nearly ten years. Despite his association with hotels at Angledool he remained teetotal all his life.

Back in 1972 I asked Mr McCarthy about the bushmen he encountered in the north west and who peopled the poetry he recited to me.

“Oh, they were … just ordinary men but they had their particular individuality. Some of them would say, instead of saying ‘G’day’ they would say ‘What won all the races? G’day’. These were the fellows who used to work for twelve months and then owe the boss something for the cheques they had drawn and put into the local town for betting purposes.”

Jim Harper expressed a fondness for race horses, seeing his first race meeting at Angledool where horse racing was very popular in those days. “I must have been a very small boy at the time,” he reflects, “for that meeting dates back to B.C (before Carbine).” [Cross, p.11] Harper is making reference to the New Zealand horse Carbine which won the 1890 Melbourne Cup. It was an epoch-making win since Carbine still holds the record for the heaviest weight ever carried by a winning horse and the field of 39 horses which he defeated remains the biggest field ever run for the event.

Perhaps the game that ‘Honest’ John Merry played was to use the old bark pub as a betting agency.

Listen to the song MYALL GROVE and read the poem.

Not everybody could live in town. By necessity, many settlers lived and worked far away from the townships. They were constantly confronted by the loneliness of their existence. Many of the jobs on the frontier were of a solitary nature too, such as boundary riding, fencing and shepherding. How one coped with the solitude faced in frontier regions is the subject of Harper’s poem Myall Grove.

The narrator has apparently cleared an area for pasture and built a ‘cosy little cottage’ in the bush, well away from the township. But the isolation and tedium of such an existence appears to overwhelm his thoughts and feelings. Despite the company of his old dog Roy, the narrator desires human companionship. This is especially so at night when “Myall Grove is laden with a loneliness complete”. To take his mind off such feelings of loneliness and depression, he “listen(s) to the night”. In so doing he gives proof to the maxim that “great gifts are bestowed in solitude”. [Robertson, W.: Out West For Thirty Years, W.C. Penfold,Sydney,1920 p122]

During his travels in Australia, the explorer Leichhardt “often lay awake listening to the noises of the night”. (Roderick, p 251) He demonstrates a remarkable sense of hearing and an ability to identify the many sounds of the night.

By passing the time in this way, he is able to endure another night “at lonely Myall Grove”.

Listen to A STRANGE DREAM and read the poem

Jim Harper was not averse to chronicling the evils that existed in a frontier town like Angledool. Drunkeness, gambling, the evils that befell the Aboriginal population and the general lawlessness that pervaded – all are acknowledged in his writings.

In the poem A Strange Dream, the narrator dreams he is searching for a deceased friend named Mulga Mick. Believing Mick to be of a similar nature to himself, he heads for the Gates of Hell, only to learn that his friend is too sinful for Hell. According to the Devil, the only fit place for Mulga Mick is Angledool, to which he is quickly directed.

The poem is similar to poems like Lawson’s The Shearer’s Dream. In Lawson’s poem, the dream is ended by the hot sun, while in Harper’s it is a large mosquito that awakens the dreamer. On the surface, both poems appear superficial. However, in each poem a serious point is being made. For Lawson it is the consideration of proper working conditions in the shearing sheds, while for Harper it is a realisation of the many evils that abound in a settlement like Angledool. The inference being made in the poem is that this town is “worse than Hell”.

Harper uses the same formula for bringing matters to an end in a short prose piece about an attempt on his life. The story is called A Tight Squeeze and also appeared in Splashes From The Narran. At the climax, just when he is about to be killed by a knife-wielding “lunatic”, he concludes the story in the following manner: “I simply did what any other man in the same predicament would have done. I woke up.”

Harper’s poem has no chorus. I made the third verse the chorus. In this verse, Mr McCarthy used the word “trimmer” rather than “sinner”, as used by Harper. (“To think that such a trimmer in this place could get a bunk.”) I have kept the word “trimmer”, which means an opportunist. Apparently it also has a slang usage, meaning a good or impressive person. I like the appropriateness of this facetious play on the word, perhaps something the Devil might have enjoyed doing.

-

Listen to the song A DIGGER’S LUCK and read the poem

The area around Angledool is popular for opal prospecting. The humorous poem “The Diggers’s Luck” concerns a prospector who dreams one day of “striking it rich” and thereby becoming an opal king. The many shafts and depressions all over this area make ideal breeding places for mosquitoes – big mosquitoes.

-

Listen to the song WHEN ANGLEDOOL WAS YOUNG and read the poem

In the front of Memories Of Angledool, Mrs Cross includes the words of an unpublished poem of Harper, When Angledool Was Young. For the song I have used only two of the poem’s nine verses. He addresses this poem to an old female resident of the town. Like much of his writing, it laments “the dead old past” when “the world was wide and ways were wild” and “Angledool was young”. These quotes come from Harper’s poem. They echo sentiments about Australia’s past which are similar to those expressed by Henry Lawson. Like many bushmen of his time, Harper would have been familiar with Lawson’s poetry. Lawson’s influence on Harper is perhaps also seen in Honest John’s nostalgia for “the roaring days on the mulga scrub”.

It is therefore an appropriate one with which to end.

In 1956 while visiting one of his three daughters in Mungindi, Jim Harper died and is buried in the cemetery there. His poetry and stories capture frontier life in “the roaring days on the Mulga scrub” in the north west of New South Wales. Expressed in the language of the day, his writing provides us with a valuable and unique insight into Australia’s past.

The naming of the bridge over the Narran River – The Jim Harper Bridge – keeps his name alive in the district he loved. I hope in some small way that the setting of some of his poems to music helps keep an interest in the work of writers like Harper, who unfortunately are often very easily overlooked. There is a definite feeling of elation in being able to sing the songs and give Jim Harper his due recognition.

© Jim Low