© Jim Low

Recently I made a return visit to two memorials along the Hawkesbury River (Deerubbin). Both commemorate the first contact between the Darug people of the area and an expeditionary party led by Governor Phillip. Phillip’s party was there to discover whether the waterways they had already named the Nepean and Hawkesbury were in fact the same river.

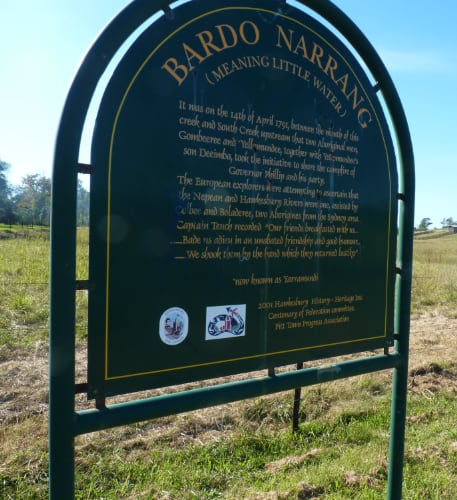

The meeting occurred on the banks of Deerubbin on 14 April 1791. The Pitt Town memorial, if I have interpreted correctly what Watkin Tench, who accompanied Phillip, wrote in one of his travelling diaries, appears to be geographically closer to the site of the meeting.

Situated east of the river, the memorial’s location is rural, the paddock adjacent accommodating a couple of friendly horses on this visit. The memorial at Windsor is located on the left bank of the river in Macquarie Park.

Being in close proximity to the waters of Deerubbin, the memorials are therefore in flood prone areas. They both are lacking signage to direct the visitor to them and are also unobtrusive in the landscape. There is a sign on Pitt Town Road at the turn off to Pitt Town Bottoms Road. It contains some comprehensive information about the area and its settlement. Although it refers to Phillip’s visit in April 1791 no mention is made of his meeting with the Darug people.

The memorial is situated on Pitt Town Bottoms Road and is now shaded under a tree. When I last visited in 2014 the tree was smaller and the memorial was more exposed. The metal frame of a signpost nearby is minus its former comprehensive account of the memorial’s significance. It had informed us about the friendly meeting that took place there and included relevant quotes from Tench’s diary. I am unaware how long the sign has been missing and whether a replacement is planned. The only other signage at the turn into Pitt Town Bottoms Road directs the visitor to ‘historic Pitt Town Bottoms’.

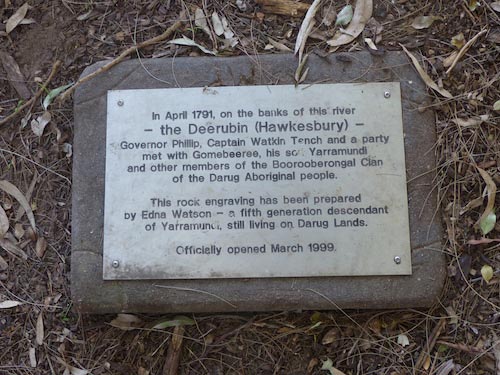

The Windsor memorial has nothing to inform the visitor of its location. It took me a few visits before I eventually found it last year. On my last visit, I had with me a free information map entitled Macquarie Trail which was published by the Hawkesbury City Council in May 2011. Any indication of these two memorials was absent from this visitor resource.

Years ago I read a poem by Amy Cumpston entitled The Old Corroboree Ground.

If we desire ‘to honour the past from certain desecration’, she warned, ‘for fear of the tourist, leave the place forgotten’.

This warning was directed specifically at examples of indigenous presence such as ceremonial sites. But should memorials, like the ones under discussion, also be just left ‘drowning in the bush’, doomed to ’the scornful void of history’? I read Cumpston’s poem again on returning from the Hawkesbury and it saddened and disturbed me.

The memorial at Windsor has a significant indigenous component, the rock carvings being made by a local Darug woman. On a small rock outcrop, the simple representation of the first contact by feet impressions is very effective.

I was pleased to notice that since my last visit the site has been cleared of undergrowth and there have been some new plants established around the memorial. These simple improvements help to enhance its importance.

At Pitt Town there was unfortunately only evidence of dereliction. Besides the missing sign, the rough sidetrack in front of the memorial is not an encouragement to stop there. Bardo Narrang (Little Water) Creek nearby, a place where the sight of domestic waste apparently is not uncommon, was choking in weeds.

Memorials are sited in a landscape because presumably there are those who believe that they are worthy and valuable representations to perpetuate some significant historical memory. The initial impression one makes when visiting a memorial is therefore very important and can depend on a number of variables. These include such things as clear direction and access to the memorial, appropriate information acknowledging the significance of its representation, and evidence of the memorial’s maintenance rather than neglect. Negative impressions can unfortunately influence the perception of a memorial’s importance.

I believe that the Windsor and Pitt Town First Contact memorials, although unobtrusive in their presence, commemorate a very significant event that took place in our shared history soon after 1788. If these memorials are deliberately overlooked and allowed to go unacknowledged, how can we ever expect people to know and learn from the past?

The historical event memorialised at Windsor and Pitt Town informs and/or reminds us of a lost opportunity that took place in our history. In his travelling diary Tench referred unconditionally to the indigenous people whom they meet in this area as their ‘friends’. When they parted company the next morning (15 April) Tench wrote that ‘they bade us adieu, in unabated friendship and good humour … we shook them by the hand, which they returned lustily’. We are reminded of this behaviour on the Pitt Town memorial by the inclusion of an embossed sculpture of two hands shaking. Not far away is Friendship Bridge, another reminder. This bridge spans Bardo Narrang Creek.

The violent clash of these two cultures. whose first contact was characterised by friendship, would soon eventuate when the new arrivals began taking land in this then frontier region. I am left to reflect upon the possible consequences that could have resulted from such an initial, friendly contact made prior to this near Deerubbin’s waters.

REFERENCES:

- Cumpston, Amy: The Towers of Earth, Elizabethan Press, Sydney 1969

- Tench, Watkin: Sydney’s First Four Years, Library of Australian History, Sydney 1979

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Historical Background to the Windsor and Pitt Town First Contact Memorials

Leaving Rose Hill early on 11April 1791, Governor Arthur Phillip led ‘a strong and numerous’ exploration party overland, intending to establish whether or not the Nepean and Hawkesbury Rivers were in fact one and the same river. The group of twenty-one people included Tench, Dawes, Collins, White and two Aboriginal men, Colbee and Boladeree. Ten soldiers, including two sergeants, also travelled with the party. They carried supplies to last ten days and were armed with guns. Three gamekeepers also accompanied them so the guns, along with the soldiers, were presumably taken for protection.

Tench detailed the trip in his travelling journal. His description of the country traversed was not always very favourable. He considered the land they encountered drab and uninteresting. Similarly, his ambivalent descriptions of his indigenous travelling companions were not always flattering, despite referring to them several times as ‘our friends’. He seemed barely to tolerate what he sometimes viewed as their ignorant, childish petulance. Then later when contact was made with people from other tribal groups, he showed a deep fascination and regard for their ability to understand a different dialect and certain vocabulary.

Time was wasted when the party headed in the wrong direction, on reaching the Hawkesbury River. This was only realised when they later climbed a rise and sighted Richmond Hill, ‘the object of their pursuit’. Those in the party familiar with Richmond Hill from previous exploration, recognised it by ‘a remarkable cleft or notch’ that characterised its profile. The Hill was nearly thirteen kilometres in the opposite direction in which they were travelling. Some of these kilometres included a frustrating detour down what appears to have been Cattai Creek, in an attempt to find a suitable crossing.

Retracing their way, they arrived at the river around mid-morning the following day, 14 April. Proceeding upstream. they were soon approached by a middle-aged Aboriginal man in a canoe. Tench described him as possessing ‘an open cheerful countenance, marked with the small pox’. He paddled over to the group ‘with a frankness and confidence, which surprised everyone’. The indigenous man presented Phillip with two stone hatchets and two spears. The Governor reciprocated with two of their hatchets and some bread. The indigenous man then led them along a pathway, following the river. Another Aboriginal man and a young boy followed in another canoe.

The first man was named Gombeeree and the other man was Yellowmundee. The boy, Deeimba, was Yellowmundee’s son. However, the relationship between Gombeeree and Yellowmundee (father and son) was not mentioned by Tench. Whether he realised that three generations of this family were represented was not mentioned.

Tench also appeared to be unaware of the leadership status of Gombeeree and Yellowmundee, and seemed reticent to acknowledge their medical skills. There seems an implied cynicism in his reference to them as ‘doctors’. This resulted from a demonstration that night when Yellowmundee performed a ceremony on Colbee. This involved the supposed removal of splinters from a prior stomach wound that Colbee had suffered. Despite being regarded very seriously by the indigenous men present, serious enough for Tench to alert Phillip to witness, Tench dismissed it as a ’superstitious ceremony’ which he thought relied on slight of hand. I wonder whether these indigenous, medicine men would have been as quick as Tench had been to dismiss some of these strangers’ religious practices and beliefs if the opportunity arose for them? Would they, for example, have regarded the practice of communion in the same dismissive way if observing Christians believing the ritual could turn wine and bread into somebody’s flesh and blood?

Other instances of unquestioning superiority over indigenous people occurred during the trip. How someone treats you can clearly reveal their attitude towards you. The two Aboriginal companions were often ordered to fetch the ducks shot by the gamekeepers. However, they were not included when it came to the ducks’ consumption. This showed an inherent prejudice towards them. Tench openly confessed in his journal that ‘little had fallen to their share, except the offals, and now and then a half-picked bone’. The woeful implication that the duck meat would have been wasted on their Aboriginal ‘friends’ speaks of a cultural attitude that thought itself above the legitimate inhabitants of this land. This erroneously entitled attitude that thoughtlessly showed its pettiness in refusing to share fairly the spoils of the country was reprehensible. It is in no way surprising that Colbee finally stood his ground and rightly refused to submit to the requests to fetch food for the other members of the party. At least Tench had to concur that Colbee’s claim was ‘too justly founded’. But such attitudes were warnings of more serious problems to come. The inhabitants of this country would soon see their land stolen from them, often violently.

The attempt to prove that the two rivers were one had to be postponed when another creek, presumably what is now South Creek, got in their way.

The incident with the ducks indicated an innate propensity by most of the British strangers to treat the indigenous people with little or no respect or equality. The future problems that were to beset the intruders who were soon to come there, with the intention of settling and farming the land, were being seeded by such behaviours. And yet these early contacts in the Hawkesbury showed the indigenous people’s behaviour to be the reverse. Consider how Gombeeree and his people met and immediately interacted with the strangers in such a friendly and helpful way. Gombeeree, before parting, even felt comfortable enough to demonstrate his skills in tree climbing.

Another example of friendly behaviour which was shown by inhabitants of this area was mentioned by Tench when he and Dawes ‘completely settled the long contested point about the Hawkesbury and Nepean’, finding them ‘to be one river’. They accomplished this in May, the following month. Leading a small party and only accompanied by a sergeant of marines and a private soldier, they proved that the two rivers were the same. Ever since his first sighting of the river at what is now Penrith in June 1789, Tench never underestimated its serious potential to flood. This trip was no different and at one stage he remembered that the river’s ‘sudden rising (was) almost beyond computation’.

Tench included an account of the local indigenous people assisting them in crossing the Hawkesbury River near Richmond Hill. They had met a man named Deedora who showed ‘every mark of benevolence’ towards them. He offered to ferry them across the river in his canoe. At one stage during the crossing , one of the Aboriginal men was left for a time on his own with some of the party’s equipment, including three exposed guns. Despite some anxiety on Tench’s part when he realised this, nothing amiss happened. Incidentally, Deedora knew Gombeeree, whom Tench referred to as ‘our friend’.

It was a very serious oversight that these initial examples of friendly behaviour by the local Aboriginal people were not fully recognised and developed by the British. Knowledge of the area’s cultural significance to the local people may have worked to help understand their reactions when land grants began. Behaviour could have been modified and solutions reached co-operatively. But the inherent attitudes of the British intruders were already determined.

Reference:

Tench, Watkin: Sydney’s First Four Years Library of Australian History, Sydney 1979