I guess we are losing what once could be considered an inherent value in land travel. The value of the journey is being devalued by the life-is-a-race philosophy. The journey is seen as an encumbrance between the start and finish. Speed, we are continually warned, when we take to the highways, is a killer. And our appreciation of a journey across land is dying with each new fast car that rumbles off the assembly line. We no longer take time to enjoy the distance travelled. If we take a break, it is usually an enforced one, hopefully to ensure our safe completion of the journey.

As a child, the most common form of transport was by foot. We knew our territory intimately and this knowledge made us more aware of the details of the landscape in which we belonged. We knew the many characters who peopled our area. We knew its unique features, its colours, its distinctive sounds and smells. We were more attuned to change in the landscape. We had a sense of place.

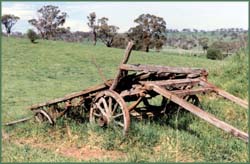

As our ability to cover land distances increased, so our appreciation of distinctive features and changes in the landscape declined. Today the 220 kilometre trip from Sydney to Bathurst can be comfortably made in around three hours by car. In 1822 when the Hawkins family travelled to Bathurst by horse, cart, dray, and wagon, as well as walking, it took them eighteen days.

When Mrs Hawkins later wrote to her sister back in England describing this “tremendous journey”, it is no surprise that she had plenty of information to relate. Her letter provides a valuable documentation of the family’s travels over the newly-built Blue Mountains road. Slow travel, through landscape described by Mrs Hawkins as “never intended for human beings”, provided the family with an enforced opportunity of familiarization. They became aware of the topography, the native flora and fauna, the sounds and smells of the country they soon would refer to as their home.

When Mrs Hawkins later wrote to her sister back in England describing this “tremendous journey”, it is no surprise that she had plenty of information to relate. Her letter provides a valuable documentation of the family’s travels over the newly-built Blue Mountains road. Slow travel, through landscape described by Mrs Hawkins as “never intended for human beings”, provided the family with an enforced opportunity of familiarization. They became aware of the topography, the native flora and fauna, the sounds and smells of the country they soon would refer to as their home.

Imagine such an account being written by a present day Hawkins family travelling to Bathurst by car. It would probably contain a few lines, with the highlight perhaps a breakfast stop at Lithgow’s big yellow M. Any awareness of the landscape traversed would be rather sketchy in detail.

When visiting Tilba Tilba on the far south coast of New South Wales a few years back, I was aware of the considerable distance between the township and the cemetery. A funeral back in the days of horse and cart would have provided considerable time for the mourners to reflect upon the deceased’s life and to be aware of the countryside, as they slowly journeyed to and from the graveside.

Over the last four years I have had occasion to drive to Melbourne via the Hume Highway about a dozen times. There are so many interesting little towns along the way. Not to have stopped at them, now that I am familiar with their unique characteristics, and in some cases their histories, seems beyond comprehension. Yet the temptation to take some time and leave the highway, is apparently not strong for many others. Jugiong, Chiltern, Glenrowan, Violet Town, Euroa and Eldorado to name a few now special places, have enriched the journey. They are not just country towns. Like autumn leaves that blanket the ground, their charms are many and varied. They have afforded me opportunities to slow down, reflect on the distinctive features of the landscape and hear the variety of stories such places have to share. In so doing they have now become part of my story, my life’s journey, and I consider myself richer for this.

Over the last four years I have had occasion to drive to Melbourne via the Hume Highway about a dozen times. There are so many interesting little towns along the way. Not to have stopped at them, now that I am familiar with their unique characteristics, and in some cases their histories, seems beyond comprehension. Yet the temptation to take some time and leave the highway, is apparently not strong for many others. Jugiong, Chiltern, Glenrowan, Violet Town, Euroa and Eldorado to name a few now special places, have enriched the journey. They are not just country towns. Like autumn leaves that blanket the ground, their charms are many and varied. They have afforded me opportunities to slow down, reflect on the distinctive features of the landscape and hear the variety of stories such places have to share. In so doing they have now become part of my story, my life’s journey, and I consider myself richer for this.

In a newspaper article in August, 1998 (Sun-Herald, 30/8/98), Peter King, the head of the Australian Heritage Commission wrote:

“When you travel around this country you realise how diverse is its natural and cultural environment, and how important for our development and sense of community is our heritage.”

In his book Cradle of Incense (June 1978, p85), which tells about the Australian mint-bush (Prostanthera), George Althofer related the following incident:

“Back in the 1940’s … I chanced on a series of low, sandstone ledges above a small peat swamp near the foot of Cherry Tree Hill at Running Stream on the Mudgee Road. There, ensconced in wet rock crevices, grew a tiny species of Prostanthera … Some years later, when passing this spot, I paused for a few brief moments to renew my acquaintance … Alas for my hopes! There was not a plant left. The peat moss in the tiny swamp was dead and the creek had been fouled by cattle, which highlights the insecure hold so many of our plants have of life.”

For an observant, caring person like Althofer, his 1940’s visit provided him with a point of reference for his return visit. He was quickly able to notice the change that had occurred in the intervening years. Most often today the problem lies in our inability to detect these changes, sometimes even the big ones, because we have not taken the time to notice what was there in the first place. We have no point of reference so we are not aware of the loss. We have no sense of loss because we have no sense of place.

The changes do not necessarily have to be as subtle as the one referred to by Athofer for us to be unaware of them. It could be the closure of a local picture theatre or cafe, the painting over or removal of an old advertising sign, the loss of families from a district, the cutting down of a significant local tree or the demolition of a railway station. The changes are infinite and they impact upon the natural and cultural landscape.

For a number of years I have fiddled around with the thoughts now expressed in the song, They Don’t Have Time. During time spent in February 1997 on the south coast of New South Wales visiting places like Tathra, Tilba Tilba , Eden and Boyd Town, and later during April in Central Victoria in the Maldon and Castlemaine area, the germs of this song started to grow.

I made a note in relation to Maldon which read:Old country towns, the stories you could tell.

To wander in a cemetery lost in thought

And read of a life summarised by two dates.

At the same time I remembered a line from a song I had written about my father:

When life was less of a race.

I have always been fascinated by the concept of time. The idea of slowing down time, of taking the time from long distance travelling to familiarise oneself with a new landscape and its stories, had already resulted in a number of songs about places. Over the years, the importance for me of doing this increased.

The fleetingness of time passing and with it the unnoticed changes, deserved further consideration. And what a shame the stories which straddle the two dates on a gravestone are possibly gone forever! A field trip in north-west New South Wales with Rob Willis in July 2001, recording people’s stories for the National Library’s Oral History Collection, provided more food for thought.

Other lines written on the return trip home from Central Victoria and up into New South Wales in 1997, expressed the rush of travel with little time to stop, except for essential breaks.

From the haze through the windscreen

Across a dry, bleached plain

Flat, unending,

And no sign of rain

Dusty paddocks, no green in sight

What town will we be in tonight?

A stop in Deniliquin, for a quick cup of tea

Then it’s on to the town of Jerilderie

Let’s make Narrandera and call it a day

And wash the dust of the journey away.

And that is basically what we did. We actually had to cut our journey short and return home quickly to the Blue Mountains, as our younger daughter was reported sick.

All of these ideas came together down in Victoria in early May 2003 and returning home I finished the song in the same month – a song that had been waiting to be written for a number of years. The idea expressed in the chorus of putting your feet firmly on the ground dates back to my childhood experiences which started when I first walked over my homeland: the sense of belonging to a place, of being acutely aware of change to that place and the sense of loss occasioned by such change, and the realisation of the influence that place has over you and will always have throughout your life.

© Jim Low

Jim Low is a singer/songwriter and published author. His background is in education and he has also developed learning materials for the NSW Department of School Education. His passion is Australian history.

EMAIL: jim@jimlow.net WEBSITE: jimlow.net