© Jim Low

In 1972 I purchased a copy of Alex Hood’s Boomerang Songster No 1, Australian Folk Songs. It contained songs from Alex’s LP recording The First Hundred Years, which included the song The Exile of Erin. This convict lament, its setting the foot of the Blue Mountains at Emu Plains, had caught my attention when I first heard Alex’s recorded version of it. There had been a penal settlement established at Emu Plains in Governor Macquarie’s term in office. In April 1827 there were over 134 convicts housed there.

As I started learning to sing Australian traditional folk songs, I made a point of including The Exile of Erin in my repertoire. I actually remember finding it quite difficult to learn, much of this having to do with the quaint words and phrasing. The words appeared to be written by someone familiar with the area about which they wrote. The writer earnestly professes his innocence of any wrong-doing, especially against his country of origin. He bemoans his unjust treatment and the resulting separation from loved ones. He expresses a deep love and home-sickness for Ireland.

Until I started writing my own songs about the Blue Mountains in the early 1970s, The Exile of Erin was the closest song I sang which had a connection to the place where I lived. It soon became apparent as I read more about Australian folk songs that the chances of this song surviving through an oral tradition were pretty slim. I also discovered that the words of this three-versed song were from a five-versed poem fully titled The Exile of Erin, on the Plains of Emu. They were printed in the Sydney Gazette on 26 May 1829. The song was later set to an Irish tune. The only clue to the author’s identity was the letter M, under which was the word Anambaba.

Earlier this year, while researching early settlement along the Hawkesbury River, I discovered that Rev John McGarvie, the first Presbyterian Minister of the Ebenezer Church at Portland Head, was the author of The Exile of Erin. He wrote under various initials (M, A.B, C.D) and from what appear to be fictional places (Warrambamba, Marramatta, Anambaba).

It is possible that McGarvie’s poem was influenced slightly by Scottish poet Thomas Campbell’s poem of the same name. Campbell’s Exile of Erin was apparently based on the experiences of an Irish exile whom he met, while touring Germany in 1800. Besides similar sentiments expressed, the only lines from Campbell’s poem that have similarity with McGarvie’s include the following:

‘Sad is my fate! said the heart broken-stranger’

‘But, alas! in a far foreign land I awaken’

The plight of the convicts at Emu Plains perhaps reminded him of the poem and he used it to inspire his own.

John McGarvie was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1795. The son of a shoe-maker, after graduating from university he became a school teacher. However, his dissatisfaction with teaching led him to consider the call of the ministry. At the same time Rev John Dunmore Lang was in Scotland, having returned from Australia specifically to find a suitable minister for the Portland Head congregation on the Hawesbury River. John McGarvie had been recommended to him as a possible candidate. Prospects for such a calling in Scotland were scarce at that time, so it is not surprising that McGarvie considered Lang’s offer and accepted it. Ordained for the ministry at Portland Head before leaving Glasgow, he arrived in Australia in April 1826.

A church had been built at Ebenezer in 1809 by the Presbyterian settlers of the district but no regular minister preached there. The Ebenezer church not only lays claim to being the oldest Presbyterian church in Australia but also the oldest church.

A gifted writer with knowledge and interests covering a wide range, John McGarvie soon began to contribute poetry, articles, reviews and letters to The Sydney Gazette. When the Sydney Herald commenced publication in April 1831, McGarvie contributed enthusiastically to it. His brother William was one of the paper’s three proprietors.

McGarvie had come to the isolation of Portland Head, part of a penal settlement, and was ministering to a small, unknown congregation in a ‘Temple in a Wilderness’. It must have been a very difficult adjustment for him to have made. Not only was he away from the familiar but he had left behind the intellectual stimuli that the populated Glasgow had offered him. At first he was also separated from family and friends. Writing would have provided him with a satisfying outlet for any personal regrets, especially when documenting exciting achievements and talents found in his newly adopted home.

This seems to have been the case in March 1829 when he wrote a lengthy, detailed letter to the Sydney Gazette enthusiastically informing readers of the launch of the Australian. Built by John Grono, an enterprising member of McGarvie’s Ebenezer congregation, the ship was launched just a stone’s throw upstream from the church on the banks of Grono’s farm. McGarvie proudly claimed that the Australian was the largest ship ever built in the colony and its timbers were all locally sourced. These ‘Colonial materials’, as he repeatedly stated, consisted of blue gum, black-butted gum, iron bark and apple tree. Except for the last, these timbers appeared in his poem The Exile of Erin, also written in the same year. I do not believe this was a coincidence. As previously stated, McGarvie had a keen enthusiasm for knowledge and he did not appear to limit his interests. In a short time, he had obviously gained a considerable amount of knowledge from Grono regarding shipbuilding and the local timbers used. In his letter he was then able to write with authority and an eye for detail when it came to describing accurately the Australian. And likewise, the mention of the local trees also gave a certain authenticity to his poem set at Emu Plains.

The convict-built Great North Road began construction in the year of McGarvie’s arrival in Australia. While at Portland Head McGarvie possibly ventured downstream to observe for himself the considerable scale and building achievements of this new road. McGarvie’s favourable reactions to the previously mentioned publication of another newspaper in 1831 and the highly skilled talents of locals like John Grono were apparent. Such instances must have started to reassure McGarvie that this rough and ready, strange land definitely had an exciting potential of which he could play an important part.

While at Ebenezer, McGarvie moved into a newly purchased manse at Pitt Town. The Old Manse, as it is known, was originally built as a farmhouse around 1820. The farm and house were purchased in 1828 by Lang, on behalf of the Ebenezer Church trustees. It became home for John McGarvie and subsequent resident ministers at Portland Head up until 1877.

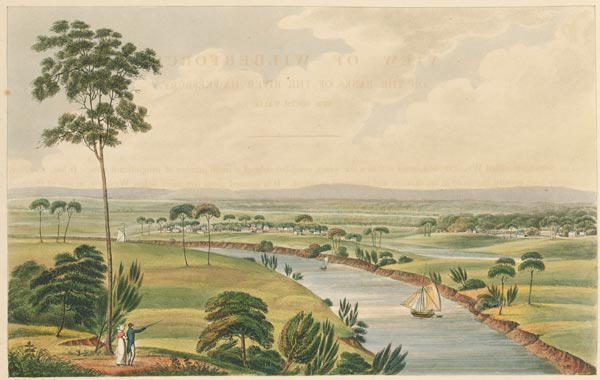

A hand-coloured engraving by Joseph Lycett was published in London in 1825.Old Manse Farm todayd View of Wilberforce, on the Banks of the River Hawkesbury New South Wales, it was composed by Lycett on an incline, just above the site of the Old Manse Farm. The land in the foreground of the engraving is on the eastern side of the river and is part of the farm.

The farm also had a punt situated on its border with the Hawesbury River. This punt provided a convenient public access across the river to Wilberforce. A pathway followed the river down to Ebenezer. McGarvie and members of his congregation made use of it. McGarvie actually commissioned John Grono to make a new punt to replace a former one that was no longer in use. In a letter to Sir Thomas Mitchell, the NSW Surveyor-General in April 1832, McGarvie stated that he still owned the punt.

John McGarvie ministered at Ebenezer until 1831 when he moved to Sydney to begin a new Presbyterian church in Kent Street, St Andrew’s Scots Church. He remained there, never marrying and died in April 1853.

In 1940 a memorial wall tablet to McGarvie was dedicated and unveiled at Ebenezer Church. The Windsor and Richmond Gazette (7 February 1941) reported on this ‘Memorable Occasion’. The current minister Rev Charman described McGarvie as ‘a great and good man’. After the Moderator General of the Australian Presbyterian Church, Rev John Flynn, who was also well-known as ‘The Flying Doctor’, presented and dedicated the memorial, McGarvie’s grand-niece Mrs McKay unveiled the bronze tablet. Rev Flynn then addressed the ceremony, giving an ‘eloquent eulogium’ to McGarvie. He referred to a newspaper article (Australian 13 August 1839) reporting on a dinner given by McGarvie’s Sydney congregation in his honour.

It says something very favourable about McGarvie’s character that parishioners and friends from his old Portland Head days also attended this function. They contributed to the ‘beautiful silver vase containing 200 sovereigns and a gold watch and appendages’ presented to McGarvie.

Flynn also spoke of McGarvie’s role in helping found the Sydney Hospital and of his literary achievements. He quoted from an article written on the centenary of the Sydney Morning Herald which stated that McGarvie had lived ‘a most illustrious and useful life’.

© Jim Low September 2015

View of Wilberforce, on the Banks of the River Hawkesbury, NSW

Joseph Lycett ca. 1775-1828 engraver

Source: State Library of Victoria