The Deua River begins its U-shaped course to the coast in the wild mountain ranges that finger out from the tablelands towards the NSW south coast. The clear descending waters commence their seaward voyage in the area of the Bendethera caves, once an isolated farm, now part of a national park. The Deua (pronounced by the locals as ‘Jewie’) runs over water-polished stones and -rocks, dropping in elevation every so often as it tumbles over bubbling white water rapids to the waterhole beneath. On its journey seaward the river picks up the waters of smaller, often not flowing, tributaries. When the Deua joins with the Araluen Creek it takes the name of the town near its entrance to the sea – it becomes known as the Moruya River.

A few rugged kilometres upstream from that confluence is Moodong Creek, a tributary that generally keeps flowing after the many smaller feeder streams stop, that runs into the Deua.

However, dry times even see Moodong become a chain of small leaf- and bark-stained waterholes. Going up this creek one finds that the stream is fed by very high and steep mountains, in places too steep for cattle and horses.

After many kilometres the V-shaped valley opens up into a Y-shape, providing many protected acres suitable for grazing. This area was known as Cudgeegamah, shortened in recent years to Cudgee.The sheltered valley is surrounded by towering mountains that reach up to the high country of the tablelands and in earlier days was connected by a bridle track that ran from Dempsey’s Emu Flat station all the way down through Cudgee valley and along to the Deua.

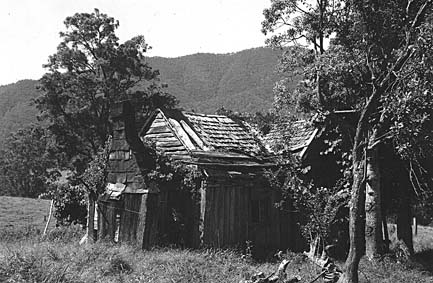

Cudgee hut [c1961] – Harvey John Davis built this slab dwelling in the very isolated Valley called Cudgeegamah for his daughter ‘Nellie’ Davis in 1908. The walls and floor of the ‘L’ shaped building were built of slabs split from the tall, straight red gums trees in the neighbouring bush, as were the shingles for the roof. Before weathering darkened the shingles this type roof gave the appearance of being constructed of red tiles. This photo was taken in 1961 or ’62 when the building was still complete but within a few years the ravages of time and white ants reduced it to just one room. Careless campers burnt down the one remaining room in about 1980. So remote was this hut that the fruit of the large and ancient grape vine that overgrew it and the adjoining trees would seldom be enjoyed by any human visitor. Those that came late in the season could smell the fermenting grapes from some distance and it was obvious to the traveller that the birds and foxes had been the sole beneficiaries to a bountiful crop in this forgotten garden in the wilderness.

While rearing her two-year-old son Everett, Helena Eliza Davis (commonly called Nellie) built a vertical slab house in that remote valley in 1908. With the assistance of her father Harvey Davis, an L-shaped house was constructed consisting of split slabs for the walls and flooring, and shingles for the roof. The slabs and shingles were split from local timber, and it was said by the infrequent visitor in those early days of the dwelling that the shingles cut from red gum made the roof look like red tiles. A grapevine was planted there in those early days. The old vine is all that survives today. By the late 1960s the ravages of time and termites saw the old house reduced to a remaining single room, the kitchen. Iron roofing replaced the shingles, the walls were patched up, fencing wire strained between a kurrajong tree and a corner post corrected the lean of the structure for a while, but the inevitable happened sometime in the late ’70s or early ’80s when the place was no more.

Nellie’s daughter Neta was born in that secluded valley in 1909. Later she would recall how, as a child, she would excitedly attempt walking around the top rail of the stockyard. With no permanent human company other than her mother and brother, Neta’s development was centred on the day to day activities of a bush block cattle run. Occasionally there would be the excitement of a visitor. Always there was the surrounding bush, mountain slopes and wild animals. Such a remote area was forever under threat from rabbits and dingoes. It would be much later that kangaroos found their way down from the higher, more level country and became a problem. Then the redneck and black wallabies were also threatened to some marked degree by their larger relative.

Packing out wattle bark from the upper Deua River (1930s) – The dried bark suplemented the income of many a bush battler and was sought after for the tanning of hides. In the spring or summer bark was stripped from the black wattle trees that grew thickly along the river, cut into lengths of about 3 feet (0.9 metre) and stacked against logs to dry. The bark would curl as it dried and when completely dry the bark would be cut into small pieces and filled into bags that would be placed in the pack-saddles and packed out. It took ten pack-horses to pack out about 1 tonne (two hundredweight per horse, a hundredweight each side).

Neta became familiar with horses and cattle at a very early stage, as she and Everett were the only constant support her mother had. The only way in and out of the valley was by horse or foot and all supplies were carried in by packhorses. It would be the 1950s before a rough steep track was formed by later owners to carry four-wheel drive vehicles into Cudgee, replacing the old bridle track. By that time Neta and her mother were living at Woolla, a place on the Deua River several rough kilometres above its confluence with Moodong Creek.

In 1919 Nellie gave the bush away and tried life in the city of Sydney. Two years later she and her two children headed back to the bush.

At one stage she lived at the junction of Moodong Creek and the Deua River. Here, as at Cudgee, and later at Woolla, kurrajongs trees were planted and still survive. They were probably planted near the houses to provide some shade for both horse and human, as the peppercorns of the inland were.

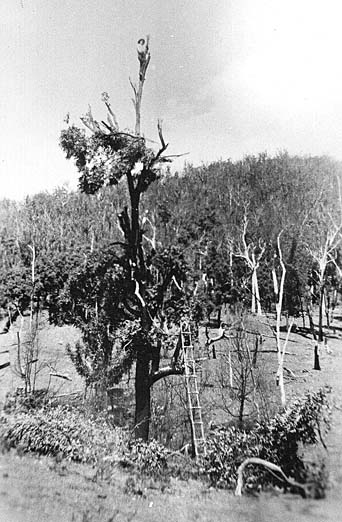

Myrtle Davis posing at top of apple box tree after lopping to feed cattle following a severe bushfire which left only four apple box trees unburnt, Woolla; 1952. Note ladder made from round bush timber

As she raised her children and worked the difficult and remote bush blocks Nellie became admired as a very capable woman, but a hard person. Local oral history tells of Nellie travelling a mob of cattle past the Araluen hotel and riding over to speak to some men she knew who were having a drink under the verandah. Andy Keys, a property owner and local councilor said, ‘Nellie, that horse of yours looks pretty knocked up’. To which she replied, ‘If you’d been between my legs as long as this horse you’d be knocked up too’. In later years men were to become very respectful of Nellie and her abilities with stock and in the bush, and with her stern reputation, gossip developed her image into a woman that men should be wary of. Some even said that if a man went near her home she would take a shot at him. Of course legends often have little to do with reality, and no man was ever shot at. The simple fact was that as Nellie grew older she preferred to stay at Woolla, keeping to herself in her bush isolation – a certain scenario to start uninformed tongues wagging.

In 1925 Neta moved with her mother and brother to take up Woolla, a picturesque bend on the Deua with towering rock-faced Beamer Mountain nearby. As at Cudgee, a house was built from the surrounding timber, this time of horizontal slabs. Corrugated iron for roofing was brought in on a horse-drawn slide over country so rough and steep that a four-wheel drive vehicle could not manage the tortuous track into the homestead sight until the 1960s. Nellie and her two children cleared the land, built the fences from logs they split themselves, mustered, branded, marked and drove their cattle out to market. Their horses were very important to them and Neta became an excellent horsewoman, winning many awards at the Araluen Sports events over several years.

In 1928 Neta’s brother Vern was born at Woolla. Sometime during the ’30s Everett left home and went timber cutting on the north coast of NSW. Neta and Vern remained at Woolla working the place with their mother. In later years Vern would go off to work at clearing scrub for landholders out from Braidwood. He spent time as a dogger around Cooma for the Southern Tablelands Dingo Destruction Board and picked peaches in season at Araluen. This outside work supported Woolla, which needed all the assistance it could get during leaner times.

Before the Davis family acquired their first motor vehicle in 1950 (which had to be left in a shed on a neighbouring property some rugged five kms away) all loads in or out were by packhorse. In earlier times Neta would ride down the Deua River to Waddell’s on the Moruya Road every three or four months to meet the mail then pack supplies back to Woolla. To supplement their income wattle bark was cut, dried and also packed out. Wattle bark was used in great amounts by the tanneries in those days.

Musterers at Woolla stockyards (c1935) – (l to r) Dick Dempsey, ‘Top’ Hassell (standing), Billy Turnbull and Vic Storker. These men, and others claimed that the Woolla women would shoot past them on their horses after the men had drawn their reins when mustering cattle in rough country. (“Top” Hassell was of the same family as Thomas Hassell, the first native born Anglican priest in the colony of New South Wales. Thomas was known as the “galloping parson” because of the many hours he spent in the saddle attending his pastoral duties.)

Other than riding, Neta became adept in the shoeing and handling of horses. The Davis women – Nellie, Neta, and later Myrtle, Neta’s daughter, – became renowned for their horsemanship, and respected by all in the district. Vern was a rider but never the horseman that the female members of his family were. A very tall, lean and gentle mountain man, Vern’s long legs earned him great respect by all able bushmen that knew him. His long easy strides would leave many good walkers well down the slopes as he headed up those steep hillsides along the Deua.

At one stage sheep were tried on Woolla and Neta found them an exciting challenge, including the shearing of them with hand shears. Mutton was also a welcome change to their diet. The experience with sheep was short-lived however as dingo attacks drastically reduced the sheep numbers, bringing that venture to an early conclusion.

Other than a visit to a dentist on one occasion, Neta actually spent thirteen years of her life without going to Braidwood, the nearest town. (During those years Neta did visit the Araluen valley, which was more of a spread out community than an actual town.) The Rankin sisters of Bendethera would ride their horses up over the mountain to Gundillion on the upper Shoalhaven, change for a dance then ride home the following day. Nellie denied Neta this enjoyment; subsequently her main socialising occurred during cattle musters and kangaroo drives when people would come together, as folk of the mountains do when extra hands are needed. A ‘gather up,’ Neta would call the get-together, ‘it was always a sort of playtime, mustering time,’ she said. Other than new faces, mustering brought the excitement of shoeing horses, repairing yards and preparing packsaddles and other gear. The evenings would be spent around a crackling fire in some mountain hut.

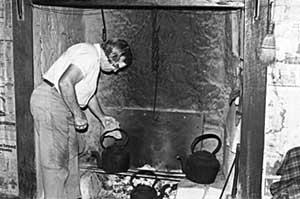

Neta Davis of Woolla (January, 1981) – Neta lived at isolated Woolla most of her life and for extended periods. Except for a quick visit to town for dental treatment, Neta spent thirteen years in one stretch out in the bush. Shown here in her kitchen which had an open fireplace, over which camp ovens and cauldrons were suspended, Neta’s mother, Neta and brother Vern, lived the same life as earlier pioneers. As was traditional, slab huts had their inside walls covered with newspapers to prevent wind coming through the cracks between the slabs and to supply pictorial diversion. The Illustrated Sydney News was a popular newspaper for lining the walls as it provided, as the name implies, a good collection of graphics to adorn the inside walls. In readiness for Christmas and the New Year it was customary to remove the old paper, which by now would have been browned by fire smoke and fly marked, and paste up the new in readiness for another year.

Colourful incidents of past musters would be retold, more recent news would be shared, joyful laughter would travel out beyond the lamp-lit camp into the dark bushland and dissipate along the gullies and creeks and echo back from the steep slopes towering overhead. Following the muster cattle would be walked out to sales somewhere. These were sociable and exciting times for Neta.

Life was often difficult. In later years Neta said that life was more difficult than it had to be because of her mother’s austere ways. However, fighting bushfires, droving their cattle across the tablelands during times of drought, lopping scrub for feed, battling the dingoes, rabbits and roos that threatened their existence were, like others who know the bush life, experiences that had to be accepted. There was no stove in the Woolla kitchen; the open fire with its large cast iron kettles and camp ovens was her life-long cooking facility. Kangaroo skin rugs lying on beds and bunks were not uncommon sights in the huts along the Deua. Neta’s skills also included the tanning of hides by using the time-tested wattle bark method.

At one stage Neta joined a cantankerous Anglo mare of hers with an Arab stallion hoping to breed out the disagreeable nature of the mother. Unfortunately the gelded offspring retained the trait of the mother. Riding the grey gelding and leading another saddled horse through the mountains one day when she was in her early 50s, the horse started bucking wildly then bolted madly down a gully and threw Neta into the rocks and uneven ground. Then, in her own words: ‘… and when I hit the ground it busted my head open and the horse turned then and backed onto me and kicked me underneath the eye with his back foot, breaking one of the bones in my face and splitting my lips off. I came to after some half-an-hour or two, an hour or so I laid there. The ground was covered with blood all around me.

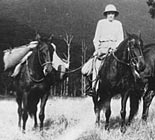

Myrtle Davis (left) and her mother Neta (1909 – 1990) arriving back at Woolla, having picked up their stores and mail from Waddell’s on the Araluen-Moruya road (1948). Until recent times all stores and materials could only be taken into or out of Woolla by packhorse.

I scrambled to my feet and went and caught my horse and made for home.’ Suffering shock and losing blood Neta led the horses up a hill where the recalcitrant gelding played up again when she tried to lead it through an improvised gate which was little more than a brush panel in a fence. Mounting the quiet horse and leading the rogue, Neta made for Moodong hut (where she and Myrtle lived for many years), where she let the horses go, tied up her dogs, washed herself and changed out of her blood soaked cloths. There were some wattle bark cutters there who took her to neighbouring Yang Yalley station, from where Kevin Griggs rushed her to Braidwood hospital. Over time the facial injuries became less apparent, fine scars being the only obvious evidence of a terrible experience.

Nellie died in 1977 at the age of 92. Everett, who served in the RAAF during WW 2, then resided in Sydney, passed away in the mid-1980s. Myrtle has her own well-managed, improved cattle property in country not so far from Woolla in distance, but light years away in terrain and productivity. Vern, now 73, is a resident in a Braidwood nursing home where he enjoys the constant company of other residents, visitors and the comforts of the town – television to watch and an electric powered scooter to travel the side roads and pathways of Braidwood. There now stands a double brick residence in Cudgee.

Neta, a woman who lived in a pioneering environment all her life, died in 1991. No more will the staccato reports caused by the crack of her whip or the firing of her twenty-eight inch barreled shotgun resound throughout the gullies and crags of the mountains. She is remembered fondly by those that had the good fortune to have shared experiences with her and she would rest easily to know that her beloved Woolla has changed little since her passing. The lyrebirds still call in the gullies, the odd dingo sometimes trots furtively across the flat below the house in the early morning shadows, cattle still graze across the small river flats and scatter along the sides of the hills, as do the wallabies. Riders using the river bridle track call in as they pass to yarn to the new owners. The eels, bass and platypus still feed in the river and the wedgetail can still be seen souring in the air currents above. Neta would be happy to know that the present owners of Woolla intend to maintain the original home and out buildings and keep the memory of that pioneering woman alive, a tribute respected by all who knew her.

© Chris Woodland

About the author

Chris Woodland has had a life-long interest in Australian folklore. While his hair was still brown he worked on outback cattle and sheep stations and maintains those earlier associations.

Chris Woodland has had a life-long interest in Australian folklore. While his hair was still brown he worked on outback cattle and sheep stations and maintains those earlier associations.

For many years he has made field recordings (housed in the National Library of Australia) of many bush personalities, including (Aboriginal and white) drovers, shearers, isolated women, poets, songwriters singers, veteran soldiers etc. Over the years Chris has been an active member of the Sydney Bush Music Club and Monaro Folk Music Society. He has been a presenter over many years on community radio 2XX in Canberra.

He retired to a few acres near Termeil on the South Coast of NSW in 2002 and then a few kilometres away to Bawley Point in 2015. For several years he ran a course called Wallaby Stew at the Milton-Ulladulla University of the Third Age.

Chris produced a book of historic photos with text on the old gold town of Araluen for the Braidwood & District Historical Society, which has sold well. It was published in 2015, followed by another book published in the same year titled Billy the Blackfella from Bourke, relating the fascinating life of his deceased mate.

Chris now spends most of his time with grandchildren and singing and playing with friends. His group is called AusSongs.