Boyd’s Tower is situated on the southern headland of Twofold Bay, above the Seahorse Shoals, on the far south coast of New South Wales.

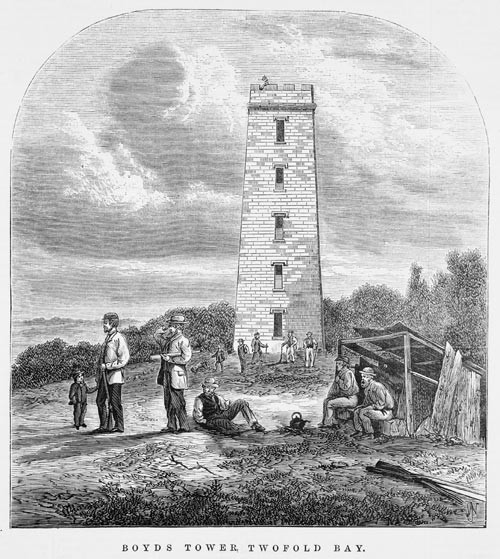

Just over four decades after the fleeting visit made by Bass, a five storey, sandstone Tower graced the southern headland. This four sided Tower displayed at the top of each of the three sides which faced the water the capital letters BOYD. Indented into the stone and coloured in black, the name Boyd could be clearly read. This imposing construction rose to a height of some twenty-three metres. It advertised to maritime travellers that they were now entering the commercial empire of a London stockbroker named Benjamin Boyd.

Although never completed, the sandstone Tower still testifies to the skill of the many tradespersons who worked on it. It also reminds us of the physically backbreaking work involved in a structure of such imposing height. Whenever I have walked around and entered the Tower during my visits over the last twenty or so years, I have never felt the structure in any way threatening to my safety.

At the time of the Tower’s erection in late 1846 and 1847, Boyd had already established a town nearby in Twofold Bay. Bearing his name, Boydtown was to be the centre for his ambitious, commercial enterprises which included whaling, pastoralism, financial and maritime pursuits.

Previous to the Tower’s construction, Boyd had directed that a tower be built on the headland and a lantern placed at its summit. A large tree was modified for this purpose. Its branches were removed and the trunk was braced with wooden poles which were fixed with iron bands. Its visibility was increased by painting the wood white and the iron black. Not a lighthouse as such, its purpose was to indicate clearly just where the entrance to Boydtown was on the coast. Prior to familiarity with the coastline and the availability of accurate charts, it was sometimes a hit and miss venture when sailing these often dangerous waters.

Alexander Weatherhead provides us with some examples from his own experience, in his memoir Leaves From My Life. When sailing with his family to Twofold Bay in the early1840s, the crew engaged the services of an Aboriginal man to act as a pilot ‘as they did not know where the bay was’. However, their pilot became confused and thought they were at Twofold Bay when in fact they were only near Bodalla. When they did finally arrive at Twofold Bay, the crew took some convincing to believe that they had actually arrived.

On a later trip, Weatherhead travelled from Sydney with a cargo of sandstone which had been quarried there. These dressed, sandstone blocks were being shipped to Twofold Bay where they were to be be used to build the hotel at Boydtown. Despite Weatherhaead thinking he recognised Twofold Bay, the vessel sailed passed it. He was supported in his belief by three stone masons who had also previously travelled there. However, as Weatherhead reflected in his memoir, he ‘could not see anything to make (himself) sure of it’.

Boyd’s Tower would help provide a solution to this uncertainty. It was originally intended to be a lighthouse. Each block of sandstone that went into its construction was quarried at Pyrmont in Sydney. The stone was pre-cut, numbered and shipped from Sydney on Boyd’s own steamships. As mentioned above, he had previously done the same thing with the sandstone required for the Boydtown buildings. Offloaded at East Boyd jetty, the stone blocks for the Tower were then transported, two at a time, by bullock wagon. This was a difficult and expensive enterprise, by any stretch of the imagination. Unused stones can still be seen scattered on the ground as you approach the Tower. Grouped in pairs they appear to lie where they were originally tipped from the bullock wagons.

Because of his many other enterprises, Boyd delegated Oswald Brierly, the manager of the East Boyd whaling station, to supervise the construction of the Tower. During the build, Brierly and Boyd kept in contact by letter. A crude gantry system was apparently used to haul the blocks into position, doing away with the need for scaffolding. Stonemasons were employed to dress the sandstone blocks. Access to each wooden level or ‘staging’ was by ladder. Serious consideration must have been given to safety as there appears to have been no death or serious injury during the build.

The Tower failed to satisfy an official inspection and was never completed. It was only ever lit briefly three times. From 1848 the new Tower gave Boyd’s whale crews a significant advantage over rival ones. They began to use it as a convenient lookout for whale spotting until Boyd’s financial failures and his subsequent departure from Australia in 1849.

From 1860, Alexander Davidson and his family began shore-based whaling from Kiah Inlet in Twofold Bay. There he built a boatshed and tryworks. He also placed lookouts at the Tower. A gunshot was fired or smoke signal sent to warn the boat crews in the bay when a whale was sighted. Photographs show a rough shelter was constructed against the base of the north facing wall and nearby a fireplace was constructed from three of the unused stones. The latter can still be seen today.

A visit to Kiah Inlet today gives a very different impression of what things would have been like in the hectic days of whaling. The gentle lapping of the water and the picturesque expanse of beach is now in sharp contrast to when whaling was operating there.. The smells which emanated from the try works, the noisy activity involved in the dissection of the whales and their blood and parts subsequently polluting water and beach, can now only be imagined.

The ever present dangers involved in whaling are highlighted by a carved inscription in the stone ledge at the bottom of the ground floor northern window of the Tower. It is a memorial to a young Norwegian oarsman from a Davidson whaling boat.

‘In memory of Peter Lia,

who was killed by a whale,

September 28, 1881.

Aged 2 _’

Over the years, it has become difficult to read Peter Lia’s age. He was probably 22 or 24. Two small crosses have also been carved on each side of this window. The incident resulting in Lia’s death occurred at night. The whale, on being harpooned, apparently towed the boat eight miles out to sea. If the harpoon rope had not been cut, things could have been even grimmer than they tuned out to be. Sadly, Lia’s body was never retrieved. He was the only employee known to have lost his life while whaling for the Davidson family.

The condition of the Tower’s stone work is still good, despite the weathering of some small sections. Sometime during the first two decades after its construction the Tower suffered lightning damage to the top of its south-west corner.

In his 1988 Boyer Lecture, the late Professor Manning Clark confessed that in his volumes on Australian history, his ‘scenes with ordinary people were niggardly in number’ when compared to those written about ‘the mighty men of renown’. I was reminded of these comments when visiting the Tower in early 1997. BOYD’s name is in large letters on top of the tower whereas the name of Peter Lia is not so clearly visible. It looks as though it was hand chiselled into the window ledge by one of his workmates. This observation led to the writing of the song Boyd’s Tower which tells the story of Peter Lia’s death.

The Ben Boyd National Park Bicentennial Project described the Tower that sits prominently on the southern headland as ‘the most extravagant in scale and construction of the buildings Boyd erected at Twofold Bay’. From this it could legitimately be argued that this expensive, uncompleted and unused structure is a monument to its namesake’s folly. Perhaps it is more realistic to regard the Tower as a testament to the many unnamed tradespeople and workers who built it. Their skills and labour resulted in a solid, well-built, enduring edifice that speaks volumes for their accuracy, precision and strenuous efforts. We should also include in this testimonial some other unsung ‘ordinary people’, namely the whalers who put their lives on the line each time they ventured out from Kiah Inlet in chase of ‘the giants of the icy deep’.

© Jim Low

Jim Low is a singer/songwriter and published author. His background is in education and he has also developed learning materials for the NSW Department of School Education. His passion is Australian history.

EMAIL: jim@jimlow.net WEBSITE: jimlow.net

- Read the lyrics to Jim’s song about Boyd’s Tower

- Listen to the podcast, Boyd’s Tower at Twofold Bay