© Jim Low

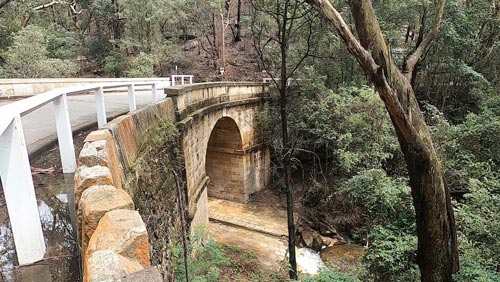

We came to live at Glenbrook, in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales, towards the end of 1973, just before the birth of our first daughter. Our home was in Glenbrook Road which joined Mitchell’s Pass. A pleasant walk down the Pass brought us to Lennox Bridge, the old convict-built, sandstone structure named after its builder David Lennox.

At this time Mitchell’s Pass was closed to through traffic and metal safety railing blocked both approaches onto the bridge. It had been moth-balled like this since December 1962 when it was deemed structurally unsafe to use. The heavy loads which it had accommodated over many years had finally taken their toll.

I used to enjoy cycling down to the bridge and exploring the site. To have this piece of colonial history in our backyard was indeed special. My family would often go for weekend walks down to the bridge, accompanied by our two little dogs. The Pass followed a creek and memories of these walks are still treasured. We would often stop and explore the convict stone embankments, culverts and drainage systems that protected the road from excess water.

Further down the Pass on the eastern approach to the bridge, there is a dressed stone mileage sign. Cut into the rock face next to the Pass, it provided distances from Sydney and Parramatta. William Weston, a member of Lennox’s convict gang, was apparently responsible for the stonework and engraving. Unfortunately today, part of the milestone has been deliberately damaged and it hides behind weeds as if to avert further harm. That’s how we value our heritage these days. Weston is also thought to have done the two wedged-shaped keystones on the bridge arch.

With the closure of the bridge and the eastern approach of Mitchell’s Pass to the bridge, this historic precinct became the ideal spot for people to pollute and vandalise. Many cars, some stolen, found their final destination in Brookside Creek, the body of water which flows under the bridge. Angry letters to the local paper documented this recurring pattern of anti-social behaviour.

I can remember visiting the bridge and seeing a very polluted Brookside Creek frothing excessively with escaped effluent from a sewerage discharge outlet upstream. It was difficult trying to explain to my younger daughter why such a thing should have been allowed to happen.

In 1975 I started making weekly trips to Sydney every Monday after work. In those days I was teaching at Tregear in the Mt Druitt area. In Sydney I attended a series of evening lectures on folk song which were conducted by a young, enthusiastic Warren Fahey.

One night, while walking to my car to start the long drive back to the Mountains, I passed the imposing Queen Victoria Building. For many years the City of Sydney Library had been housed in part of this enormous structure. It was there I had spent many enjoyable hours as a high school and university student seeking out reference books. The building, opened in 1898 on the site of the first colonial markets, had been reprieved from demolition in 1971. This grand, old building stood derelict and boarded up, waiting with uncertainty for a promised expensive ‘face-lift’.

As I walked by the old building that evening I was reminded of Lennox Bridge. Surely, I mused, it was also a structure of significance and deserved full restoration. Both the Queen Victoria Building and Lennox Bridge had uncertain futures, being dependent on sufficient finance to achieve their restoration. Likewise, the original function of each of these structures had been removed.

I remember deciding that night that I would attempt to write a song for the old bridge. Perhaps I could also have been inspired after hearing songs from the LP recordings played earlier in the evening by Warren and sourced from the shelves of his Folkways shop in Paddington. Whatever the motivation, I remember the excitement I felt that night and the realisation forming that this could lead me down a path of unlimited possibilities for songwriting material. At that time I had been unsuccessful in discovering any traditional folk songs related to Blue Mountains history.

Lennox Bridge gained State Government financial backing, having its reopening in 1983 neatly coinciding with its 150th anniversary. The Queen Victoria Building did eventually get its seventy to eighty million dollar restoration ‘face-lift’, reopening as Sydney’s premier shopping arcade in March 1984. Most of the sandstone used in the restoration of both these structures came from the Gosford Quarries.

And what about my Lennox Bridge song? I completed it in November 1975. This was also the same month that I began singing on alternate Friday and Saturday evenings at the Pioneer Way Motel restaurant at Faulconbridge.

The first stage of the bridge’s restoration work began around the time when I wrote the song. Scaffolding and supportive wooden structures were erected before the old road fill across the bridge deck was removed. This exposed the sandstone arch, in preparation for the construction of a concrete road decking to protect the archway.

Finance for this part of the work came from a National Estate grant and a New South Wales Heritage Council grant. As I understood it, the total finance for the bridge’s restoration was still unsecured. I alluded to this in my original song lyrics:

‘promised renewal, but perhaps too late’.

I used to travel down to Tregear by motorbike. Returning home of an afternoon, I would leave the Great Western Highway and head up Mitchell’s Pass, despite it being officially closed to traffic. The Pass joins the highway just before the first section of the original ascent made by John Whitton’s zig-zag railway. The highway then crossed the Knapsack Viaduct. This was before the M4 extension had reached the Mountains. I definitely found the ride up the Pass a more pleasurable and safer route. It brought me to the bridge site from where I travelled further up the bridle track beside the creek. This track leads to the old quarry from which the stone used in the bridge’s construction was cut. Some of this stone was also used in the restoration. The bridle track then crosses a small culvert, returning beside the creek to rejoin the Pass. Sometimes my wife and daughter would surprise me by meeting me at the bridge.

In 1978 I commenced teaching at Lapstone Public School. Incorporating local history in my program, I began taking classes to Lennox Bridge. These excursions occurred after the restoration work had reached the point where the site was safe to visit. They proved popular and gave the children a pride and interest in the history of their local area.

I was able to integrate different subject activities when visiting the bridge. Measuring the height of the arch, for example, using a weighted string and trundle wheel, promoted accuracy in measurement while expending some physical exertion. Some children wrote surprisingly reflective poems. Other pieces of creative writing were inspired by these visits. Wonderful drawings were also made at the site.

In 1983 I self-published a short history of the bridge, including some of the activities my students had done on these excursions. Some local schools bought multiple copies. This was very encouraging and proved there was a need for such a resource.

At the same time, I also produced a cassette of five of my Blue Mountains songs and called it Mountain Tracks, a rather clever title even if I do say so myself. Tom Christofides, a local musician and friend, was a great help with the project. I look back at some of out performances to promote the cassette with fondness. I was never happy with the final production of the songs on Mountain Tracks. It was a learning experience which helped me in later years when making recording decisions. Some other things also went wrong with the project. I had lined up a local Blaxland printer to make the cassette covers but just before I was to take delivery of my order the business was destroyed by fire.

In December 1982 I was contacted one evening by the then Mayor of the Blue Mountains, Peter Quirk. He asked me if I could gather together some of my students from Lapstone Public School to participate in the re-opening of Lennox Bridge. He had heard that I had written a song about the bridge and thought it would be most appropriate. He also said that two of the students could do the honours and cut the ribbon to open the newly restored bridge. I had my fourth grade class perform the song since they were familiar with it and the class captains were chosen to open the bridge. On Tuesday 14 December in front of descendants of David Lennox, politicians and other dignitaries we took part in the ceremony and honoured the old bridge and its builders in song.

The following year was the 150th anniversary of the bridge’s opening and an official re-opening ceremony was held. This time it was performed by the NSW Premier, Neville Wran. The state government had provided financial assistance which allowed the local council to complete the restoration work.

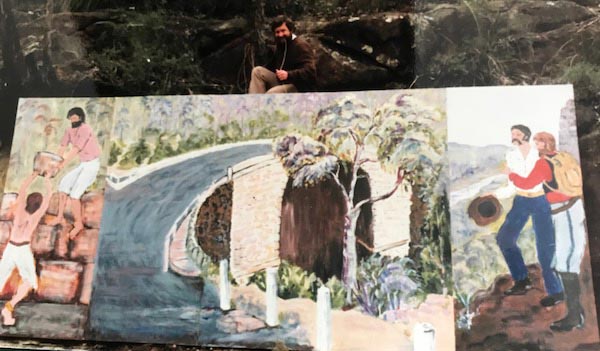

On Friday 16 September 1983 my song was again sung at the bridge, this time with a choir from Mt Riverview Public School where I was then teaching. The school went all out for the celebrations. Students, including my daughter Susannah, performed one of my poems entitled Hard Times which I had adapted for the occasion. The students also exhibited a large, painted mural of the bridge which, like the song and poem, had been worked on for a number of months prior to the occasion.

I have always found performing outside more difficult, especially when amplification is lacking. You have no control over superfluous sounds and other unannounced distractions. Despite this I was very proud of the students who participated. I was also excited that we were all now part of stories associated with the bridge’s rich and valued history. As the years pass I believe that these stories also gain in their significance. I hope the students who took part, all those years ago, look back as adults on the experiences with fondness and satisfaction. We can definitely all say that we are a part of Lennox Bridge’s story.

When culling my songs for my 2013 CD Across the Blue Mountains, I did not include my song about Lennox Bridge. It was one of my early ventures into documenting history in song but it was never a favourite and I felt it had weakness. However, I am grateful that it served a valued role in honouring the old bridge and its makers as well as teaching children to value the history of their local area. I acknowledge that this song certainly deserves a special place in my musical archive.

Over the years, I have always felt I wanted to express creatively my association with Lennox Bridge in a more personal way. In late 2019 I composed another song to honour the old bridge. It makes reference to the school excursions which I organised there and my students’ involvement in the re-opening ceremonies for the bridge after extensive restoration and years of neglect.

The bridge has been continually plagued by senseless graffiti attacks. Fortunately the local council acts swiftly on such occurrences. The site’s isolation still attracts the dumping of waste. Recently there was an old mattress in the gully.

There are many things that impress me about Lennox Bridge. The stones used in its construction have been skilfully positioned. This results in a subtle merging of both the dressed stone blocks and the coursed, rough, irregular shaped ones. The bridge appears to be growing out of the landscape. The height and beautiful symmetry of the arch never cease to amaze. Another special feature is the curve of the downstream wall. This allowed the lengthy, old horse-drawn carriages and bullock wagons to cross the deck, turning safely to continue along the Pass.

Over the years I have been intrigued by the way the road builders managed the excess flow of water around the Pass. The stone culverts, gutters and drains are definitely worth discovering. Not far from the bridge is a vertical, stone gutter that has been cut into rock. During heavy rain, I have been fascinated by the way the water from Mt Sion flows seamlessly down the roughened path of this gutter into the culvert, without any spillage. Next to this gutter is a broad arrow marking and nearby some other possible convict carvings.

You could also overlook some other features at the site. The steep, sandstone cliff walls show evidence of how the stone was removed to accommodate the road. The stone embankments that support parts of the road are also worth discovering. A visit during or just after rain will definitely show the beautiful, sandstone colours at their best. These are just some of the surprises revealed when returning to explore this historic area in the bushland.

The indigenous presence in this area needs to be acknowledged. I am unaware of the area’s cultural significance to the people whose country this is. I am also unaware of any documentation regarding relations between the bridge builders and the local Aboriginal people. In looking back over the excursion activities carried out at the bridge site, unfortunately none reference the Aboriginal people of this area.

The bridge was part of Thomas Mitchell’s upgraded thoroughfare across the Blue Mountains. The impact of this on the indigenous people proved catastrophic as more intruders found it easier to travel along the mountain road. Despite this, I feel it unfair and pointless to criticise the accomplishment of David Lennox and his team of convict bridge builders because of their alleged part in what was to come. Australia’s colonial history is riddled with the clash of cultures. This shared history happened and hindsight can sometimes be a sterile teacher. I believe this part of our history has to be confronted honestly and considered fairly. It should not be disregarded or forgotten just because it is fraught with difficulty and variably leaves one to the mercy of the history bully’s wagging tongue.

Although no longer teaching I have never stopped revisiting the old bridge. I enjoy exploring this historic and picturesque part of the Blue Mountains and I continue being excited by the things I find and experience with each new visit. The history of this old bridge has literally been set in stone.

And still you stand, for all to see

A reminder of our history

Looking like you’ve always been

Part of this Blue Mountains scene.

Jim is a singer/songwriter and published author. His background is in education and he has also developed learning materials for the NSW Department of School Education. His passion is Australian history.

CONTACT:jim@jimlow.net

WEBSITE: jimlow.net